Lexicon Financial Group Weekly Update — July 16, 2025

“Good debt makes you rich, bad debt makes you poor.”

From the desk of Craig Swistun, CIM, MFA-P, Portfolio Manager, Raymond James Investment Counsel, and Wayne Hendry, Client Relationship Manager, Raymond James Investment Counsel

ISSUE 188

Looking Around

You know the feeling you get when you look at your credit card statement? Well, governments may be getting that feeling too (or maybe not).

Why?

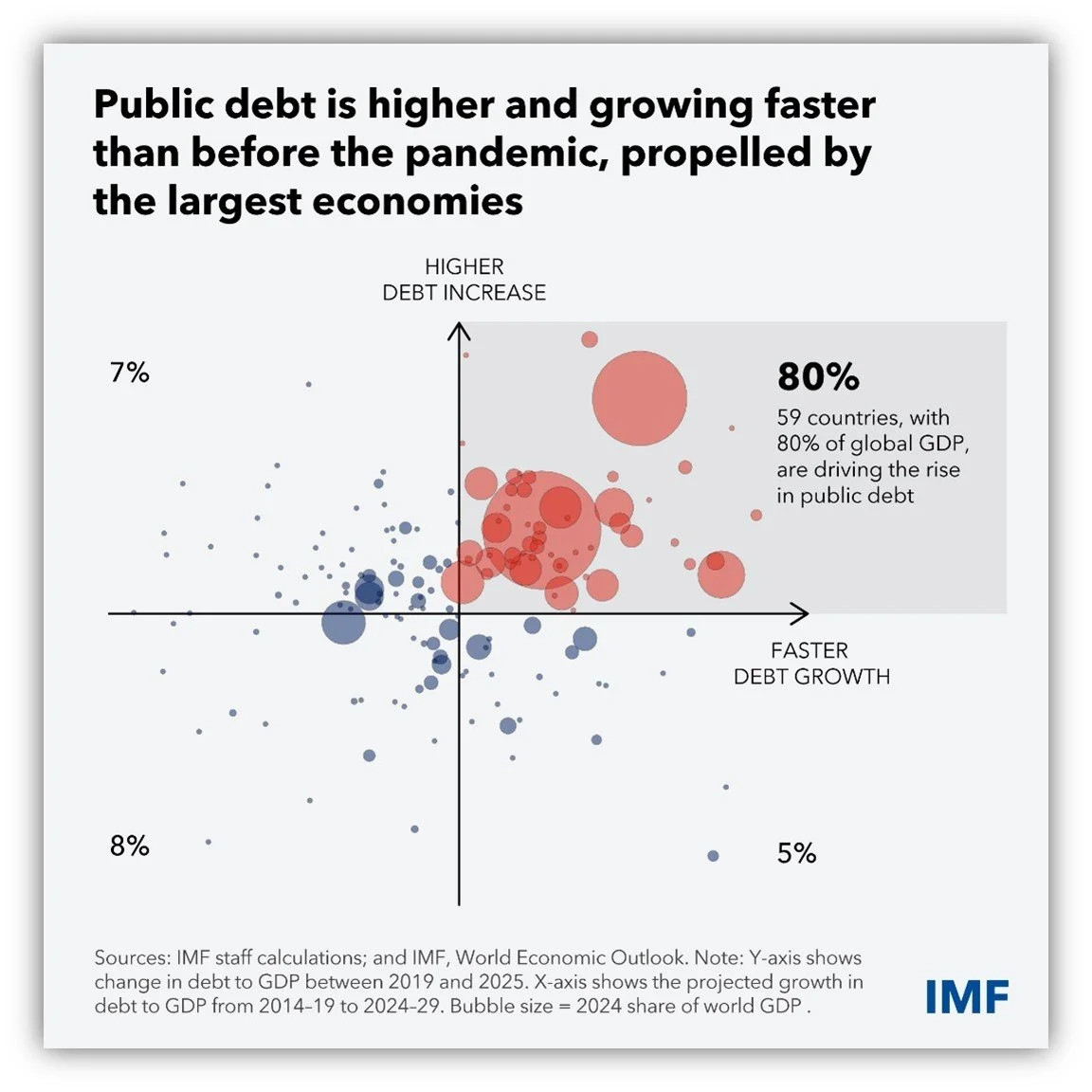

Well, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), public (aka government) debt is higher and rising faster in most of the global economy.

The IMF forsees global public debt increasing to 100 percent of global gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of this decade if current trends continue. The current rising ratio of public debt to GDP reflects renewed economic pressures as well as the consequences of pandemic-related fiscal support. The IMF belives that this trend raises greater concerns about long-term fiscal sustainability as many countries face rising budget challenges – more than two-thirds of the 175 economies in a recent IMF study now have heavier public debt burdens than before COVID spread in 2020! (1)

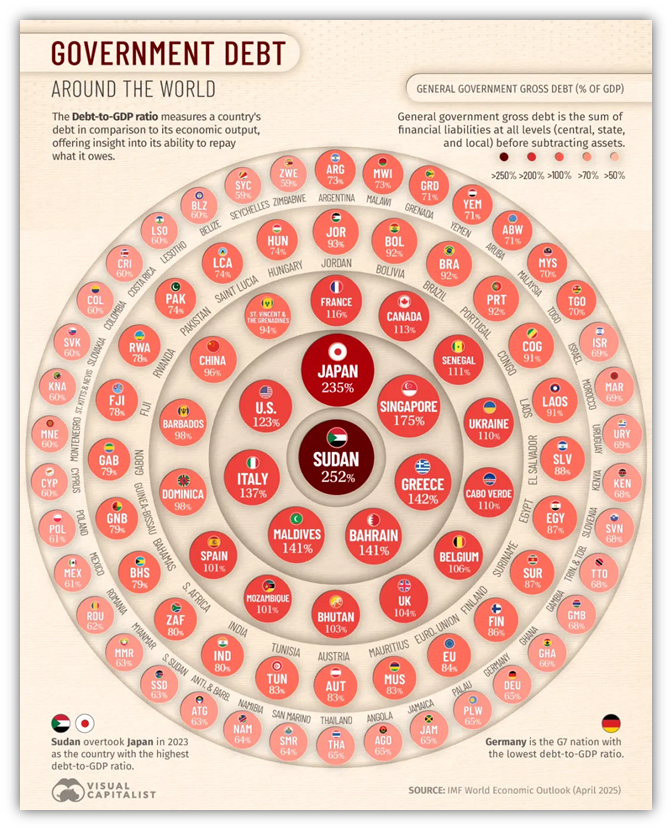

To get a better idea of the enormity of government debt to GDP ratio globally , just take a look at the diagram below:

Although there has a been a lot of talk about the high public debt of the United States (U.S.) government, Sudan has the highest - 252 per cent of GDP – due to prolonged conflict and severe economic challenges. Sudan actually overtook Japan as the country with the highest debt-to-GDP ratio in 2023 which was the same year in which the Sudan civil war broke out. And talking about Japan, it has the highest debt burden amongst developed countries at 235 per cent of GDP. The U.S. government does have a high debt-to-GDP ratio of 123 percent which reflects many years of deficit spending and large-scale stimulus policies in response to recent economic crises like the pandemic and the 2008 Financial Crises.

However, advanced economies (including those of G7 countries) are also struggling with higher debt burdens with an average debt-to-GDP ratio of 110 per cent, compared to around 74 per cent for emerging and developing economies - Canada has a debt-to-GDP ratio of 113 per cent. Interestingly, the G7 country with the lowest debt burden is Germay at 65 per cent of GDP.

High public debt levels are usually the result of various factors such as aggressive monetary policies, quantitative easing, slow or negative economic growth, and increasing public spending needs. Typically, debt-to-GDP ratios grow when governments use fiscal stimulus to counter these factors and improve economic health. While there is no doubting the usefulness of going into debt to be able to deal with economic downturns, persistent and excessive debt carries long-term risks. These include slower GDP growth, currency depreciation, larger interest costs, and, in really extreme cases, sovereign defaults that require IMF-led bailouts. Even countries like Japan and the U.S., who issue debt in their own currencies and have flexibility in managing debt loads by printing more money, face rising interest costs as debt levels increase. (2)

So it looks like that significant public debt is bad but is it? If the U.S. borrows and spends money to help stimulate the economy, launch national infrastructure projects, etc., having more debt can be helpful especilally if the return (economic growth) on this type of government spending is higher than the interest paid on the debt. The problem with increasing government debt over time is that interest costs grows as well. These costs take up a larger and larger amount of a government’s annual finances which make it harder to spend on education, infrastructure and social programs. On top of this, if a country’s share of debt grows or is perceived as too large, it may be more difficult for it to borrow money since it’s perceived to be at risk of defaulting. The telltale sign that a government has too much debt is if the yield (interest) on its bonds go up significantly as it did in the U.S. earlier this year.

Countries, like consumers and businesses, have a credit score. A lower credit score for you or us means either not being able to make large purchases using debt or do so at a very high interest rate. Investors will charge a country higher interest rates if they believe that a country has too much public debt. And as bond rates increase, so do other rates that affect us, the consumer. In the U.S., interest on student loans, home loans, business loans, etc. are based on the 10-year Treasury yield. There are several ways that a government can reduce large government debt. It can increase tax revenues through higher taxes, reduce government expenditure, or ensure that its economy is growing faster than its debt load. (3)

Just like consumers, countries eventually have to deal with public debt. Not doing so could lead to the the long-term risks mentioned earlier. Debt can be good or bad for countries just like it is for consumers.

Read and Watch

Want deeper insight into topics in your Weekly Update? Then, read and/or right click:

Canadian inflation ticks up to 1.9% in June, boosting expectations of no BoC rate cut in July

Is America Breaking the Global Economy?

‘A slap in the face’: EU leaders, industry reel from Trump’s tariff shock

Is China’s economy growing or shrinking? here’s the truth behind the data

Looking Back

President Trump ramping up his tariff assault on Canada last Thursday by saying that the U.S. would impose a 35 per cent tariff on imports beginning in August which is up from the current 25 per cent rate. Although The S&P/TSX composite index (TSX) pulled back last Friday, for the week it only posted a 0.05 per cent decline. Investor sentiment may have been buoyed by expectations that the exclusion for goods covered by the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement on trade will stay in place. And also by the news that the Canadian economy added 83,100 jobs in June and the unemployment rate surprisingly fell to 6.9 per cent from 7 per cent in May. Money markets now see a 13 per cent chance the Bank of Canada cuts its benchmark interest rate at the next policy decision on July 30. This is down from 27 per cent before the jobs data. (4)

Major U.S. stock indexes finished last week modestly lower, with the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite Index holding up the best. Although tariff news dominated the headlines last week, market reaction was muted when compared with previous tariff announcements. In single-stock news, NVIDIA hit the $4 trillion market capitalization threshold for the first time, helping put the “mega” back into the so-called Magnificent Seven group of mega-cap stocks.

Minutes from the Federal Reserve’s mid-June policy meeting released last week revealed some disagreement among members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) about the direction of monetary policy. Most policymakers said that they anticipate cutting rates this year but two stated that they would be open to rate reductions as soon as the late-July FOMC meeting. On the other hand, some committee members said that they don’t anticipate cutting rates at all in 2025. Stock markets showed little reaction to the FOMC minutes.

Across the pond in Europe the pan-European STOXX Europe 600 Index ended 1.15 per cent higher amid hopes for more trade deals between the U.S. and other countries. But market gains were curbed after U.S. President Trump said he would send a letter notifying the European Union of higher tariffs on its goods. Other major stock markets also rose.

Japan’s stock markets lost ground last week due to tariff-related developments, (notably some signs of growing tensions in U.S.-Japan trade relations) and mixed domestic economic data releases which weighed on investor risk appetite. The U.S. announced that it would implement a slightly higher tariff of 25 per cent on Japanese imports, up from the 24 per cent rate the administration set in early April. Investors however viewed positively the indication that the higher tariff will only come into force on August 1, 2025 which leaves more time for negotiations. Japan is also very focused on the July 20 Upper House election, where Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s ruling coalition is expected to lose seats, compounding political risk and upheaval. Investor sentiment was also pressured by domestic economic data which showed that Japan’s wage growth slowed sharply in May which raised concerns about the broader economic recovery and reaffirming some expectations that the Bank of Japan could delay its next interest rate hike until next year.

Mainland Chinese stock markets rose as data showing persistent deflation spurred hopes for more stimulus. The producer price index fell 3.6 per cent in June was worse than economists’ forecasts and marked the 33rd month of factory deflation, as well as the biggest drop for producer prices in nearly two years according to Bloomberg.

Although the consumer price index unexpectedly rose 0.1 per cent and snapped a four-month streak of declines, analysts believe that the increase was likely driven by recent stimulus measures rather than a sustained improvement in consumer confidence. This latest inflation report raised the possibility that China’s leaders may have to roll out more stimulus to lift the economy out of a persistent cycle of falling prices, corporate profits, and wages. (5)

The opinions expressed are those of Craig Swistun and not necessarily those of Raymond James Investment Counsel which is a subsidiary of Raymond James Ltd. Statistics and factual data and other information presented are from sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. It is furnished on the basis and understanding that Raymond James is to be under no liability whatsoever in respect thereof. It is for information purposes only and is not to be construed as an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of securities. Raymond James advisors are not tax advisors, and we recommend that clients seek independent advice from a professional advisor on tax-related matters.

Debt is Higher and Rising Faster in 80 Percent of Global Economy, Era Dabla-Norris, Davide Furceri, IMF Blog, May 29, 2025

Visualizing Government Debt-to-GDP Around the World, Niccolo Conte, Visual Capitalist, April 29, 2025,

Is the national debt good or bad? Janet Nguyen, Marketplace, May 9, 2025

TSX gives up weekly gain as the US plays 'hardball' on tariffs, Twesha Dikshit and Fergal Smith, Reuters, July 11, 2025

Global markets weekly update - Muted response to more U.S. tariffs in most markets, T. Rowe Price, July 11, 2025

SUBSCRIBE

If you’d like to automatically receive the Weekly Market Update by email, enter your email address in the box below.

We respect your privacy, and you can always remove yourself from the mailing at any time.

Looking to Learn?

If you want to know more about some of the topics we wrote about this week, just click on the links below: